... at dawn, we will be in Tokyo

Capsule purgatory in Japan, drifting spirits and arbitrary divisions.

My constant comings and goings are not a search for contrasts, they're a journey to the two extreme poles of survival.

Sans Soleil (1983), Chris Marker

During the earlier part of my summer chasing butoh in Japan, I drifted through the living spaces of some anarchist friends. These porous but well cherished places embraced me unconditionally; loving ecosystems built by comrades rooted in mutual respect and openness. Although these spaces seemed to exist in a persistent state of flux and often at risk of dissolution, a commitment towards freedom was steadfast.

In a soft hued memory of afternoon with a gentle new friend, attempting to share something I had learned in a recent butoh lesson, with broken Mandarin as our common language. I remember falling ungracefully onto the tatami, laughing as I repeated the words 放松 (Fàngsōng) in Mandarin, which means "to relax" or "let go," using my body to express its essential meaning. This simple exchange somehow devolved into both of us chanting 自由 (Zìyóu) / "freedom" and 放松 (Fàngsōng) / "let go" interchangeably as our bodies collapsed over and over, the air around us vibrating with a shared joy of release and mutual understanding that freedom is a practice of letting go.

In passing through these spaces of varying opacities, where doors were never locked and light and shadow leaked through every crevice and opening, not once did I feel unsafe or in danger. Furthermore, I was able to inhabit a profound vastness of spirit, liberated from opaque distinctions of "public" and "private", "mine" and "yours." Dialectical conceptions melted away into an indeterminable ocean of "ours". In our mundane existence together, there was no implicit expectation or obligation to reveal too much about one’s life or backstory; instead, my companions and I coexisted in shifting layers of intimacies and proximities.

Not being able to speak Japanese, my daily interactions with people were also limited to simple gestures and body language. A friend shared with me the Japanese expression 空気を読む (くうきをよむ, kuuki wo yomu), which means "to read the air— an unspoken tenet of Japanese culture intended to prevent discomfort, conflict, and feelings of shame among peers in group settings. The negative side of this is that people will assume things about you. Yet, as my friend put it, “If you can get past the initial awkwardness, you can be left alone to do or be whoever you want to be.” I am fond of this turn of phrase because it captures the essence of myself as not a solid being, but as a formless vapour or scent dispersing into the air, breathed into people’s bodies.

hilang. hilang.

One of my fondest memories of wandering Kyoto in tsuyu (梅雨), the season of summer rain, is the smell of damp wood lingering in the winding alleyways lined with historic wooden houses. This heady scent emerges when moisture from rain seeps into wood, awakening its natural oils and compounds, unearthing an earthy and comforting aroma. For me, smell is a powerful limbic trigger and serves as an evocative yet elusive carrier of time and place. Evading capture, scent drifts freely, just as spirit does.

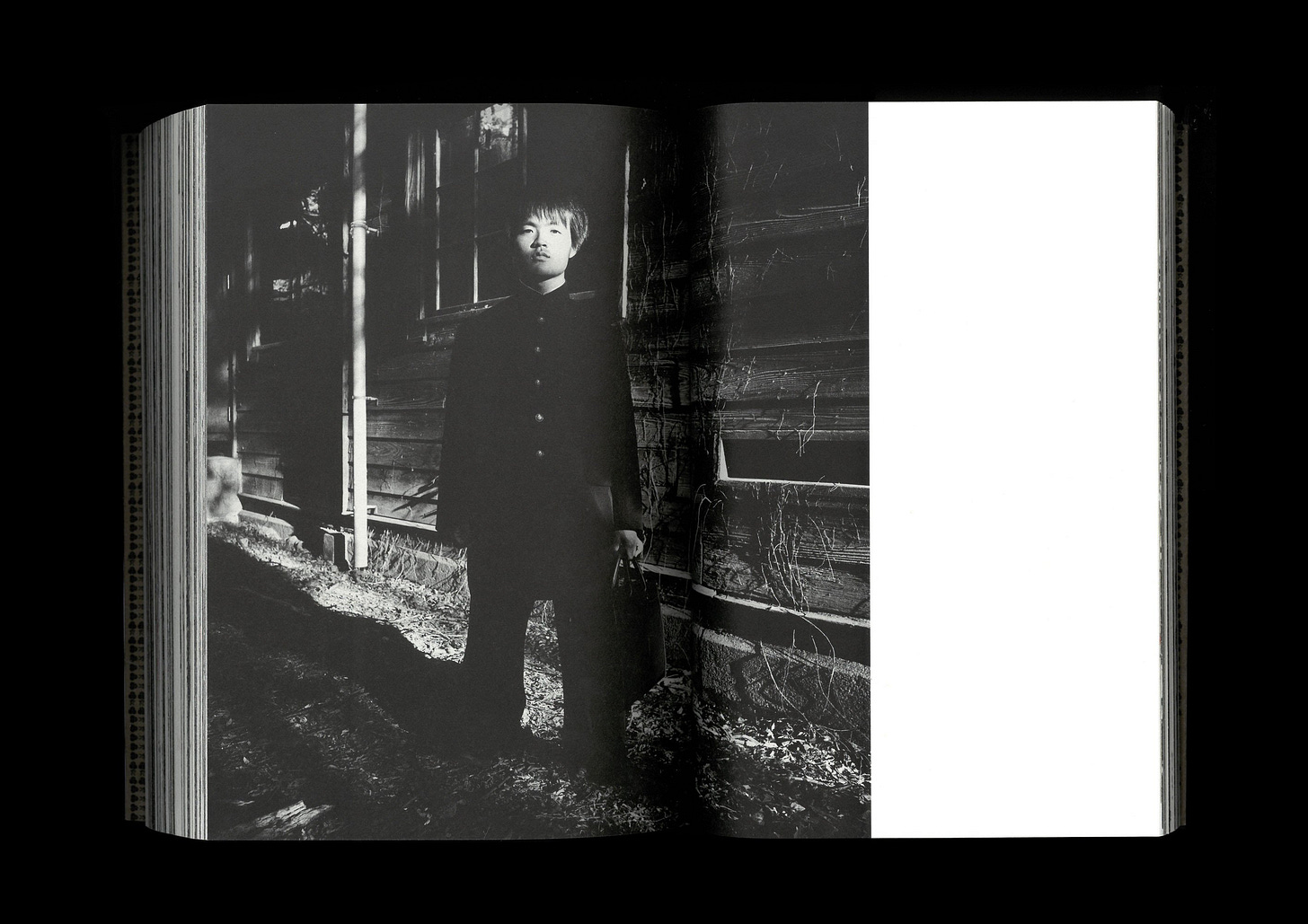

During my time in Kyoto, my friend took me to visit Yoshida Dormitory, the oldest student residence in Japan, located on the Yoshida campus of Kyoto University—one of the country’s most prestigious national universities. Run entirely by its student residents, the dormitory serves as a living example of what a self-governing, autonomous community can endure and look like in an age of unchecked power and escalating tyranny. Originally envisioned as an all-male residence for the top students of Kyoto University, the dormitory was part of a state-run imperial institution created to educate Japan’s elite. Hiroji Kinoshita, the first president of Kyoto Imperial University, built the dormitories under the belief that self-governance would bolster students’ character development1. Ironically, the aristocratic model of self-governance that was expected to flourish did not evolve in accordance with the university’s aspirations. Instead, the students, granted complete autonomy, transformed the dormitory into a nucleus of anarchic principles, youth activism, and a melting pot of alternative communal lifestyles, ultimately posing more of a challenge to the institution than a “respectable” precedent to be upheld.

Yoshida Dormitory is an autonomous dormitory where the residents themselves decide how the dormitory should be run. People of various ages, genders, and nationalities live together, and the dormitory serves as a safety net and a place to explore the future of society.

Source: https://yoshidaryo.org/archives/uncategorized/3343/

We manage our dorm democratically through open meetings and discussions. Even non-residents can participate in the running of Yoshida Dormitory and use our facilities.

Source: Save Yoshida Dormitory Brochure, Published August 2018

A labyrinthine network of seemingly endless corridors with traces of human activity spilling out from every corner, Yoshida Ryo had a primordial air of lived-in chaos. This byzantine disorder, with its sprawling ecosystem of negotiations, possessed its own circadian rhythm. This complex circuitry of intersections and nuance provided a refreshing foil to the compacted paradigm of Singapore that I was familiar with, wherein everything has its designated and incontestable place. In my country, the bodies of people are continually regulated by hostile architectural features, relentless urban planning, and social strictures, which leaves the resulting individual closed off and impervious, an opaque body.

The Yoshida Dormitory which might appear uninhabitable to the everyman, has also been embroiled in a legal battle with the university since 2019, which seeks eviction of its residents on counts of property damage and safety concerns. Residents and supporters of the dormitory believe that “the university management is threatened by our (their) system of self-governance and wants to construct a new dormitory that they can control more easily.2” Spaces that operate outside the control of a centralized authority—where individuals and groups actively exercise varying degrees of self-determination simultaneously—are often perceived as a impediment to established governance. These environments challenge conventional power structures by fostering autonomy and diversity in decision-making, leading to alternative ways of living and interacting. The existence of such spaces disrupts the uniformity and predictability that centralized governance seeks to maintain, thereby raising concerns among those in power about the potential for instability and the erosion of their control.

The closure of Yoshida would mean the end of one of the only remaining student-governed dormitories in Japan, whose role, as defined by one of the dormitory’s residents, “is to allow people to experience the freedom to live enjoyably according to the rules they have set for themselves.”

Source: https://www.theindy.org/article/3038

As the balmy summer showers passed and my petrichor-filled memories of Kyoto began to fade, time gradually took me into the dry, oppressive heat of natsu (夏), the peak of summer. Amidst the sweltering heat, I experienced a far colder and more impersonal form of transience when I stayed at various branches of the 9 Hour Capsule Hotel franchise scattered throughout Tokyo city—spaces that were indifferent to my presence, in which I was able to disappear into anonymity. Capsule accommodation was intentional, driven partly by budgetary constraints and also by my preference for a spartan, monastic existence when traveling, one that meets only my basic needs for sleep and hygiene. These hotels, tailored for overnight travelers and individuals in transit, were not meant for extended dwelling. One’s pod had to be kept empty, void of any signs of inhabitance, and guests were advised against leaving personal valuables inside for danger of theft. The capsule which I started referring to as a "plastic coffin" during my later days of capsule fatigue possessed a ridiculous requirement for all guests to vacate their pods between 10 AM and 2 PM for cleaning. This locked me into a doomed pattern of sleeplessness, in which my sense of time acquired a peculiar elasticity, underscored by a slight undercurrent of hysteria, in which I became, a living ghost.

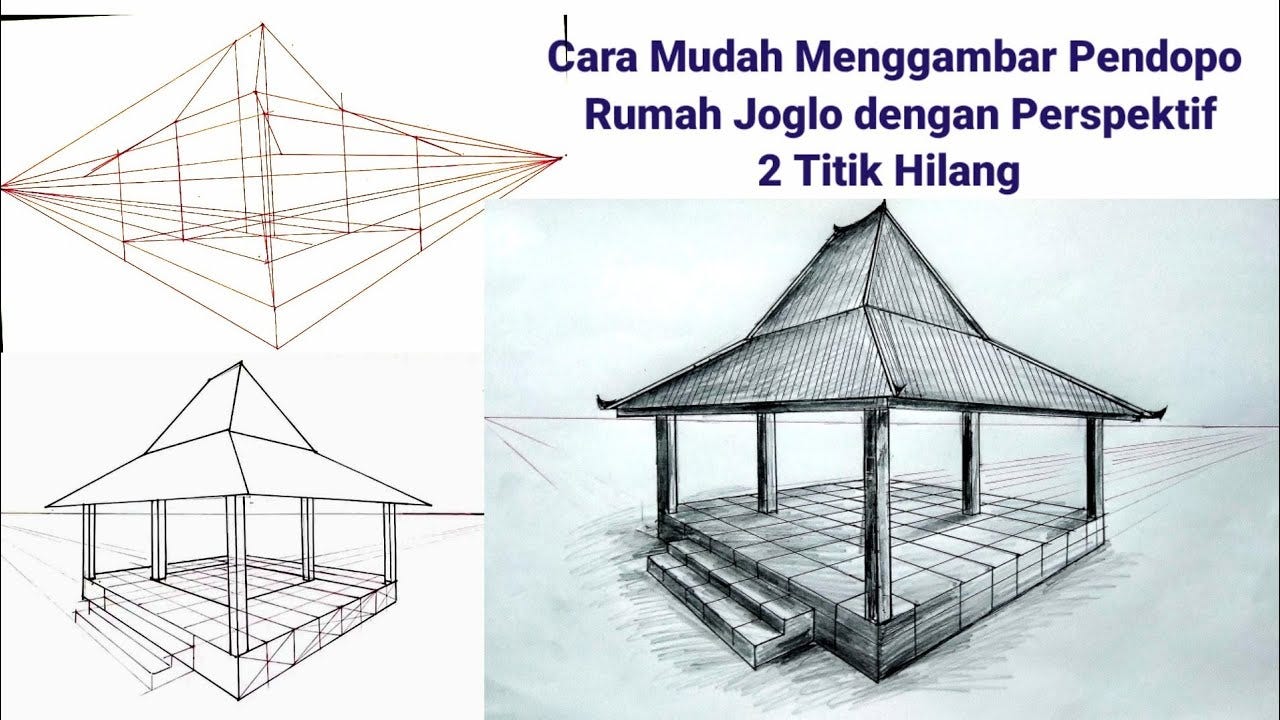

In both Indonesia and Japan, I encountered many spaces with no clear delineation between interior and exterior. The structures often lacked spatial boundaries like walls or doors. Instead, separation and place were defined not by physical barriers but by social norms, shared values, and local customs. This experience led me to question how much of what we perceive as “inside” or “outside” is influenced by environmental, cultural, political, and economic forces, rather than adhering to a strict boundary. In my capsule, where each pod was separated from the "outside" by a simple pull-down blind, I began to reflect again on these arbitrary divisions. Separated onto by this plastic membrane, my exterior environment constantly bled into my interior space, affording me no sense of privacy. A month of journeying had finally left me stationary, but nothing within me felt settled, if anything I became even more untethered.

But what a spiral man’s being represents! And what a number of invertible dynamisms there are in this spiral! One no longer knows right away whether one is running toward the center or escaping.

Source: The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard, The Dialectics of Outside and Inside

Over the years, I have devised strategies for traveling efficiently, to be a smooth operator of minimal design. Being bald is partially a vanity project but also a pragmatic decision. I have not paid for checked baggage in more than three years. I no longer carry toiletries or hair care, and my clothing is modular and easily adaptable. I can pee, sleep, and shower literally almost anywhere. Additionally, my lack of interest in food, nutrition, health, or gastronomy has its perks: I avoid food poisoning by being an unadventurous eater; I don’t spend at restaurants, as I am not food-motivated. Moreover, I’ve had my eyeliner tattooed on my eyelids three times (to get it perfect—it’s still not), allowing me to forgo buying or wearing makeup altogether. All these pragmatisms came in handy for surviving my prolonged residency in the capsule. I only ever remember having to strive to optimize myself to such olympian degrees while living in New York, a city known for being highly demanding of its inhabitants.

Not having to vie with other guests in the capsule for showers, sinks, or hairdryers, nor having to frantically rummage through a bulky suitcase full of dresses, makeup, and underwear, gave me an odd sense of superiority. Yet, I was acutely aware that there was no real glory in economising oneself. What was I truly accomplishing by being the most efficacious member of the capsule cohort? Had growing up in a meritocracy made me so performance-oriented that I would compete with strangers over who could take the quickest shower?

In retrospect, I do wonder whether my stay at the capsule had truly been such an ordeal or was it just the result of poor planning. As ‘designer-chic’ accommodation, it offered stylish facilities, clean bathrooms, and showers with hot water. Yet, the numbered pods, sleep-tracking surveillance technology, complimentary pyjama sets that made guests look like inmates, the narrow lockers for storing our belongings, and creepy automated announcement at 9:30 AM prompting guests to vacate the premises felt distinctly dystopian and Brave New World-esque. Ultimately, it all made me wonder, ‘why the fuck did I pay money for this again?’

One night, while lying in the capsule, both hypnotized yet increasingly aggravated by the hum of the central air conditioning and the incessant blipping of the sleep-tracking body sensor, I experienced a chilling epiphany: that despite all my political and counter-cultural complacencies, at the heart of it, I was the very epitome of every problematic I had been railing against.

Did the Singaporean in me knowingly choose to inhabit the oppressive conditions of the capsule? After all, Singaporeans in the name of pragmatism would literally give up all their human rights for a clean bathroom, hot water and high-speed internet. The tendency of pragmatism to overwrite all contingencies for the sake of convenience, creates a dangerous opaqueness that severs our connection to the world and the realm of possibility. An artist that aspires to be a pragmatist is really just a pessimist in disguise, for they have all but given up on chance, acceding to the comforts of certainty.

“So what is the Singapore system called? It’s called pragmatism.”

—Source: The Straits Times (Updated June 06, 2024, 05:00 AM)

Pour avancer je tourne sur moi-même

Cyclone par l’immobile habité.JEAN TARDIEU,

Les témoins invisibles, p. 36

(In order to advance, I walk the treadmill of myself

Cyclone inhabited by immobility.)

Mais au-dedans, plus de frontières!

(But within, no more boundaries!)Source: The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard, The Dialectics of Outside and Inside

The illuminating and deeply inspiring practice of ashleyho+domeniknaue could be said to be the opposite of pragmatic or programmatic, an artistic duo whose shared world manifests itself as an ongoing dialogue of living process that composes itself in real time through a series of felt choices. The pathways they set in motion, collapse boundaries between audience/performer and subject/object. In embracing all possibilities, the work sets itself free into the boundlessness of its own presencing. In one of their artist bios, both artists confess to feeling "at home and out of place at the same time" intervening in space through the role of provocateurs, voyagers and inhabitants, an incredibly compelling dynamic to witness.

When two strange images meet, two images that are the work of two poets pursuing separate dreams, they apparently strengthen each other.

The Poetics of Space (1958), Gaston Bachelard

In Ashley’s recent words, “we’ve decided to melt into the entanglements between real and art-living”. This act of total surrender allows the two to sublimate in real time the mess and mass of lived experience. By stripping away the conventional trappings of artistic production and output, their work becomes liberated from itself.

Yesterday, I witnessed a staging of their latest piece, last portrait, at the Esplanade Annexe Theatre. In the black box, a large, barren plot of earth scattered with pill bottles began to bloom as Ashley and Domenik unearthed autobiographical fragments and gut-wrenching vignettes, grappling with themes of loss and grief. For an hour, the duo tended to their garden with an earnestness and intensity that feels increasingly rare (and pure) in a landscape where performances often manifest as highly stylized affectations. I, too, have been guilty of such evasiveness; but the distances I create in my work allow me to feel safe and in control and I am not ready to let go of them yet. However, Ashley and Domenik’s intimacies dissolve these separations and reminds me that the origins of art lie beyond the polished facades of "professional" artistic creation.

Yesterday’s experience of last portrait reminded me that the potency of live art stems from a true commitment to being. In order to activate the transformative potential of performance in oneself and all those involved, one can no longer remain half-open. Performance as a form cannot be opaque but translucent and porous, to allow for leakages between the hard axises of certainty. What is precious and what is held in these temporalities is not always visible to the naked eye and the art is really in the reading 空気を読む (くうきをよむ, kuuki wo yomu) and the subsequent responding.