‘a place we could not name' [2025]

A selected project for *SCAPE Experimentation Ground | Post-show reflections

Two years ago, I happened upon a piece of writing by my friend and now artistic collaborator Razan Wirjosandjojo. While much of the contents of the essay now elude my memory, one line in particular stayed with me. I have translated it from the original Bahasa Indonesian, so the depth of expression might be lost in comparison to the original.

Performance offers a body that is closely connected to time and space, but is not imprisoned by duration. Performance offers the opportunity to be a galaxy, to ‘become a crystal’.

Razan Wirjosandjojo, Ulasan dan Opini: Kuliah Marina Abramovic “The History of Long Durational Works of Art and MAI” (Published: 2023) | Translated from Bahasa Indonesian via Google Translate

In this juncture of the timeline, Razan and I may have been acquaintances or even strangers. Yet, something in the sentiment of this reflection struck me deeply. At the time, I was grappling with an adjacent conundrum while pursuing my Masters—an epistemological reckoning of my own making.

How does one contain endlessness? … Or count every star in the galaxy? … How does one contain a total work of art? How can I trap time in the crystal? ∞ternity wants to be held tight as it struggles to break free from my/your/our embrace.

XUE, ‘eternity is the state of things at this very moment’, Masters Thesis, Lasalle College of the Arts (Published: 2023)

My graduate work, ‘eternity is the state of things at this very moment’, was a cosmo-poetic performance lamenting our finiteness in the face of infinity. Through many overlapping strategies embedded in the work, I sought to emancipate performance by approaching it through a multichannel or assemblage framework—one I equated to a crystal or prism. My attempt to integrate the Deleuzian concept of the crystal-image further complicated this inquiry—an unnecessary theoretical overlay that muddled rather than clarified. All theory aside, I was drawn to performance art’s potential as change itself—an aspect I have been exploring through various artistic experiments. Ultimately, my intention was not to communicate liminality to an audience (which I believe is already a given in any live work), but rather to confront our estrangement from it. If time or duration exists as an infinite web of relations, how, through strategies of body and space, can we render these temporalities felt or tangible?

When I say that I want to emancipate performance, I am not being facetious, I mean to really free it from a single discipline, duration or context. While I recognize the danger of making work about nothing by trying to address everything, I also believe performance holds infinite possibilities to directly unlock the depths of one’s creativity and demands a multivalent approach. I want to open up this space through the use of strange choreographies1 which embrace an element of unpredictability and randomness, allowing performance to exist in a realm untethered from formal measures.

‘a place we could not name’ is perhaps my second attempt at grappling with this predicament—this time, alongside two bright-minded conspirators game enough to navigate the abyss with me. The third contributor along for this ride was my long time collaborator Mervin Wong, a brilliant Singaporean composer and sound artist who has accompanied me on many difficult artistic propositions, with whom I also run a music label in Singapore. By some stroke of luck, our project ‘a place we could not name’ ended up being a selected project for SCAPE Experimentation Ground, an incubation space in Singapore for emerging and established artists interested in experimental performance making and performance art. Through the program’s support, we were able to test and develop our ideas about space, place and the body.

The artistic query for this work began with my experience of a punk show in Yogyakarta. Last year, my friends were eager to bring me to a gig, as they often do when I am in town. When we arrived, I was surprised—it was held at a university. That in itself was interesting, but the real surprise came when I saw the "venue" itself: a couple of pillars wrapped in cloth. No walls, just fabric stretched between posts, forming a makeshift enclosure. I remember standing there, taking it all in, and thinking to myself, "Wait, you can call this a venue?" And then came another surprise—"No smoking in the venue." That gave me pause, for there were no actual walls, just cloth. I also pondered, why did smoking on one side of the fabric count as “inside” while the other side did not? Everyone complied though, and we stood outside smoking our cigarettes, listening to the music from the bands leaking out of the space. Curious, I asked the organizer, "Why not just remove the cloth? Then we can watch the show and smoke outside at the same time." He shook his head. “Mbak, if I don’t have the cloth, how else can we charge for tickets?" That moment stuck with me. A flimsy boundary—just fabric—was all it took to define an interior and an exterior, a space existing solely by collective consensus. The idea of claiming or delineating space in such an informal manner fascinated me, it also made me think of some of the absurd state-mandated demarcations of my home country—an “illusion” of place, agreed and acted upon.

Not long after the punk show, I ended up in Solo for the summer, where Razan is based. Ever since reading his writing, I had an instinct that we could be collaborators. I thus shared the germ of the idea with him and Mervin and applied for *SCAPE Experimentation Ground, and somehow, we got it.

So in Singapore, everything in our country has a place, has a name, has a function. And so, as someone who travels a lot, I am very interested in non-spaces and non-places, things that defy containment, defy … some kind of value that is assigned by society or the state … or something like that. We wanted to make a work that kind of resisted definition.

XUE, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

So, one of the core questions of this project is what makes space into a place? As Razan suggests in our post-show dialogue, place-making is not merely a function of physical demarcation but one of meaning-making and also of choice. It is not solely about the architecture of a location but about the ways in which we inhabit it, shape it with our movements, behavior and thinking. A place is also not just mapped but felt—it is constructed not only through walls, boundaries, and coordinates but through sensation, presence, and absence. The work is asking, if a place is defined not just by structure but by the shifting conditions of our experience, then what are those conditions and how can we engender them?

Space might exist, I would feel, without our existence, it’s like you have this very big space, very big universe, but then, to call some space into a place, it’s more something about our existence, it’s also about how we put meaning into this space, it’s somehow also not really about our logical way to understand what a place is, it’s also somehow how we feel about the space, how our senses describe or define a place.

Razan Wirjosandjojo, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

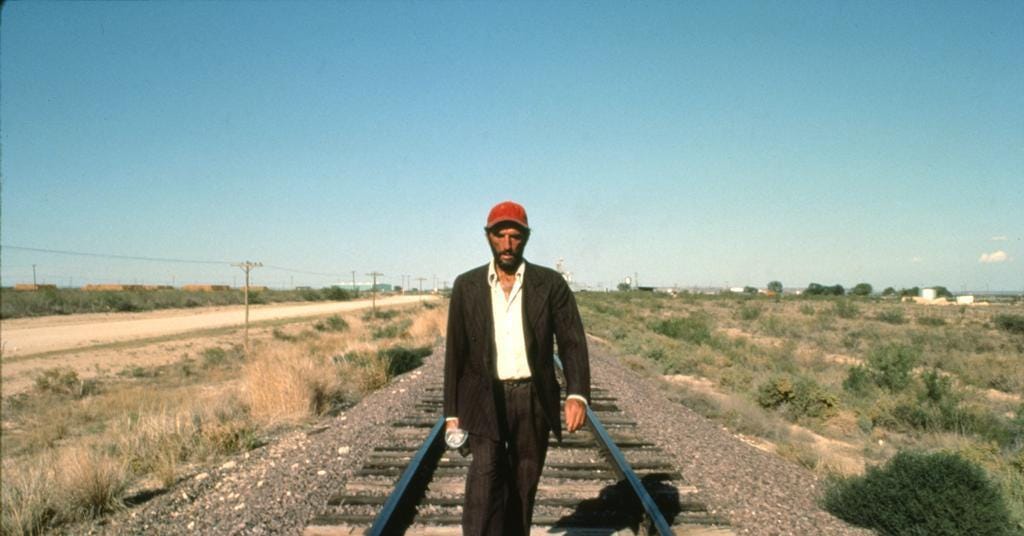

The title for the work ‘a place we could not name’ comes from the film ‘Paris Texas’ by german filmmaker Wim Wenders (1984). The movie opens with its mute and disoriented protagonist, Travis, wandering aimlessly through the American Southwest. Wenders uses the expansiveness of the desert as a type of existentialist metaphor, which resonates with our project's exploration of place-making, seeking meaning and connection amidst liminality. Working also with a sense of vastness, by forgoing traditional staging elements at the Ground Theatre at *SCAPE such as utilizing the stage area or a dance mat, we embrace the entirety of the space, allowing performers and audience members to experience the scale of the environment in its totality. This approach also dissolves expectations of a genre-specific show or conventional production. The absence of conventional frames (such as the proscenium stage) instead invokes the idea of the audience’s gaze as a kind of framing in and of itself. When someone enters a theatre, they instinctively align themselves with the space—perhaps responding to the type of work being presented or to infrastructural cues that suggest where to sit and what to face. We wanted to dissolve this bias—a resistance to a clear prompt on how to place the body.

And outside, the world seemed very quiet. All he could hear was a distant truck. And for the first time, he wished he was far away. Lost in a deep vast country where nobody knew him. Somewhere without language or streets. And he dreamed about this place without knowing its name. And when he woke up, he was on fire.

Wenders, Wim, dir. 1984. Paris, Texas. Road Movies Filmproduktion.

Both Travis and his estranged wife, Jane are missing-peoples, runaways without a clear destination. The idea of the vanishing or the missing person was introduced early in the project by Razan, who was interested in exploring the erasure or disappearance of the body and how a sense of space or place could persist even in its absence. In our initial discussions, he also proposed working with darkness—allowing the space itself to disappear. In trying to design an environment where absence and presence became integral to the experience. We contemplate, does our sense of place also disappear once the body that animated it has vanished?

In one of my favorite scenes in the film, Travis finally reunites with his ex-wife Jane, but they are separated by a one-way mirror. At some point in their interaction, their faces meet, superimposed over one another, creating a beautiful moment of convergence. For me, this scene encapsulates the optics of estrangement and raises a larger question: How do we embrace connection, knowing it will always be incomplete? The one-way mirror serves as a separator and conduit, reinforcing both distance and reconciliation.

This feature of a borderline or barrier is something we also explore in our work. Using a movable rectangular frame that we revolve and push through the space, we present the audience with the shifting image of two forms merging and separating. The frame acts as an intermediary or barrier between the bodies, which never physically touch or engage with each other in the work. As we move through the space with the frame—painted black—along with our black outfits, we create shifting impressions for the audience, allowing them to perceive a passage of transformation, even if its details remain indistinct.

Obscuring our identities and physical features was also a deliberate gesture. We made outfits specially for the work—an all-black ensemble that we decorated with various trimmings and wore throughout the performance. This disguise blurred our individual appearances in the dim lighting, making it difficult to distinguish one of us from the other at first glance, challenging the audience’s ability to track or fixate on us as we moved. A critique of our attire was that it was seen as distracting, difficult to see, or impractical. Initially, I proposed that we wear minimalist black, form-fitting outfits to emphasize shape. But Razan felt that we needed more. More of what, I wasn’t sure—but I was curious to find out. Fastidiously, we kept embellishing our garments, adding on until we were satisfied with them on a tactile level. We also designed headpieces or face coverings loosely inspired by Fu Dogs—traditional guardian lions in Chinese culture that are often placed in pairs at the entrances of buildings. There was undoubtedly an element of provocation at play, as we were aware of how bizarre the costumes would appear to the layman.

Whimsy—something I learned from the spirit of Butoh founder and provocateur Hijikata Tatsumi—is something I have always afforded in my own work. A decision born out of a simple condition of want, not something to be interrogated or made small by the artist. In art, it is important to me to follow my whims, to make choices that defy logic or good sense. In the case of our costumes for the show, perhaps we wore them because we wanted to. If I were to unpack this on an aesthetics level, I would say that the layers and textures added to the organic and inhuman feel of the work, as we became organisms or life forms within the amorphous world that we were trying to conjure.

Backtracking to November 2024, when Mervin and I flew to Solo to further develop the piece with Razan—it was the first time the three of us had spent time together or collaborated as a trio. Our process was largely trial and error, with no preset expectations. During the residency, we worked on the project for about four nights straight after Razan’s workday, experimenting and improvising with the metal frame at Studio Plesungan, which generously provided us space for our investigations. We also embarked on a fun side quest, visiting a small river and waterfall that held special significance to Razan, where we spent the afternoon climbing wet rocks in the rain.

Something about this shared experience made us reflect on how the body navigated space in natural versus civilized environments. Traveling to Indonesia to work on the piece also introduced two elements that were incorporated into our performance: a language of turbulence and locomotion—shaped by the sonic and embodied memories of Mervin’s and my varied modes of transportation from Singapore to Solo—and the image of the river.

We use motifs about the river, any river that goes into any places, water that reaches into like the nameless places of the world, places that we haven’t walked yet with our feet, places in our dreams, sounds of vehicles and trains and travel.

XUE, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

Serendipitously, Razan had earlier suggested incorporating water imagery for the concluding part of the piece, projecting footage of running water and rain within the rectangular bounds of the floor projection to contrast with its rigid form.

Our residency in Indonesia was instrumental in shaping the overarching structure of the work, which we built by collaging various discoveries about the metal frame from our sessions in Indonesia, Mervin’s field recordings from that time and my on-the-ground observations of the performance venue in Singapore.

In the following segment, I will recount the overarching structure of the work and our decision-making process.

At the start of the piece, Razan and I stand in a darkened part of the room—an audience blind spot we have identified—our hands resting on opposite sides of the movable frame. After the audience has settled in, we emerge from the darkness, pushing a frame whose wheels we have locked to create a sense of resistance as we push it across the space. The frame also emits a rattling noise as we push it, reinforcing the language of turbulence whilst traveling. The friction created by the locked wheels introduces a sense of density to the space and can thus be experienced as a material quality.

Audience members entering the space are not given instructions on where to sit, leaving them to decide where to position themselves. As they enter, they are met with the image of a "glowing square" formed by external light streaming through the door frame. Through the open door, ambient noise and other stimuli from the outside seep into the space. About two-thirds of the way through pushing the frame, I release the frame, leaving Razan to drag it alone whilst walking backwards away from me. Eventually, he too lets go of the frame and disappears into the darkness.

Intersecting about two-thirds into this passage of movement, Mervin appears, silhouetted within the 'glowing square,' holding a standing microphone. On his way to his sound station, he first traces the doorframe with the mic, then the faint rectangular patch of light that appears on the theatre floor during the 7 PM showings. His movement here is inspired by a distinct movement quality of his, which I observed while watching him take field recordings in Yogyakarta.

Then me using the field recorder and looking at it like ghostbusters or as a sonic thing, was when we were in Solo and Jogja, doing the residency for this work, I was taking field recordings in the rice fields of Jogja and because I had to be very silent and make sure my footsteps were not be picked up by the field recorder so I had to walk like that in the rice fields and I think Sher (XUE) was very inspired by that and she was like ‘I want you to move in the work like that as well’.

Mervin Wong, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

Mervin’s “space-walking” or “astronaut” movement was utilitarian but we used it in the work as a means of provoking the imagination. Mervin’s character is investigating the invisible energies of the space itself, which manifests as sound frequencies. Mervin’s scanning motion was also to draw attention to certain features of the space, like edges, boundaries and delineations. By scanning the doorframe, he designates it as a space in its own right. We used the body in space and the field-explorer archetype as a way to draw the eye to things we found interesting, that might otherwise go unobserved.

So for me it’s quite clear, my character is kind of like an explorer that is foreign to this place and planet and these two structures, I wouldn’t even call them beings, they are like structures in the space, they are part of or they are there when I reach this place so, I think I am always scanning throughout the work.

Mervin Wong, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

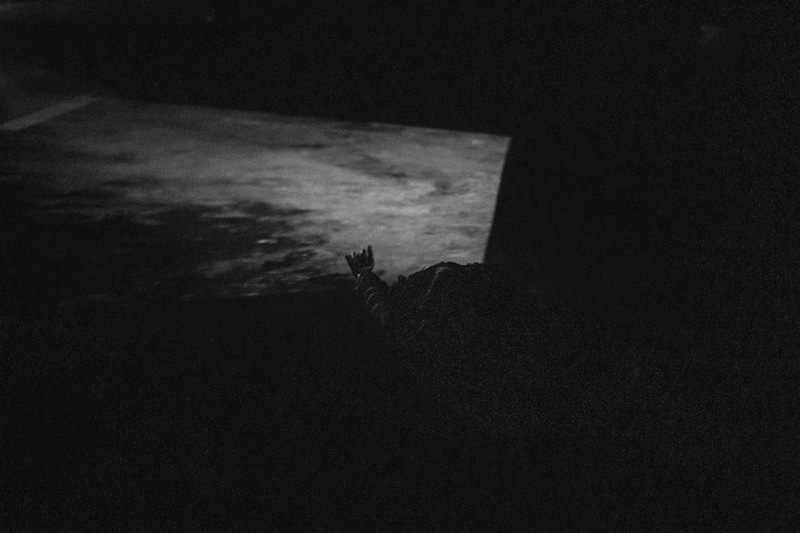

One of our key investigations in placemaking is in how one’s senses define a place. For Mervin, one of his artistic goals was to make sound a physical experience—a space in and of itself—using field recordings as memory triggers to transport the body to different places. He believes that the sonic sense affects us in a direct, visceral way, not merely serving as a passive setting or backdrop. After Mervin arrives at his sound station and Razan and I separate, the doors of the space close slowly, enveloping the room in darkness. The sound then builds into something more visceral and intense. I begin pushing the frame through the darkness, invading the personal space of the audience—sometimes moving slowly and deliberately, at other times breaking into abrupt, erratic, almost berserker-like movements. This heightened the audience’s vigilance, as there was no indication of where I would go or appear next. They could sense my presence through the rattling of the frame and my movements with it, but they could not see me clearly.

We designed the sonic configuration of the space as well so that you would be able to sense it with your body.

XUE, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

In this part of the work, Mervin seeks to fill the space with sound—to make sound a place in and of itself. Our choreography is not just about the body in motion but also about shaping the space, affecting the audience’s senses to create an experience of a place that has never existed before. This is not purely a phenomenological inquiry neither is it strictly a spatial investigation.; it also considers the energetic and emotive potential of space,

One of the questions we have received post show is: why was the piece so dark and what was the intention behind turning off all the lights. First, we intended to disarm the audience, to make them lose their sense of orientation. We also wanted to draw attention to overlooked aspects of the environment through presence—not necessarily its formal qualities, but rather by activating a different type of body sensitivity, one not dependent on sight. One of the audience members also described their experience of the piece as an “intuitive response”.

I think we are trying to present this one hour to see with your ears, you also hear with your skin, just to let the other senses have more space.

Razan Wirjosandjojo, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

After 10 to 15 minutes of complete darkness, the lights at the top of the space gradually brighten by about 3%, though the overall space remains dim. A high-tempo electronic track begins to play. Razan reenters the space by melting down from a staircase extending from stage left.

Emerging again from the darkness, I slowly push the frame through the space in an automated manner. At the sound cue of a doorbell ringing, I mechanically swing the frame open, like a door. Razan then begins his movement sequence at the base of the steps, dancing through audience members before entering the frame, as if passing through a portal.

This sequence then transitions into a game with the audience. Razan and I silently bring the frame to audience members, presenting them with the choice of stepping through the frame, as if it were a doorway. This part of the performance becomes a social experiment, using the symbolism of a door or entryway to prompt the audience to make choices about whether to participate or refuse. In this way, we are also choreographing the audience, as their position in the space becomes influenced by ours. By getting the audience to engage with this "non-space" or "empty" frame as a door, we are also inviting them to, like the concert-goers at the Yogyakarta venue, to suspend their disbelief and play along with the idea that the frame could be a door or portal, even though it visually reads as a simple frame. This shift in reason and perception is another facet of what we are seeking in the work. The audience in turn, also becomes a landscape in which we have to navigate, a place in its own right.2

Something that I also noticed, though it was not our intention persay, was that the overall atmosphere of the piece sometimes had an ominous or even oppressive quality. Perhaps this was amplified by Mervin’s non-musical soundtrack, composed of field recordings of drilling and construction noises from around *SCAPE, our experiments with the frame, as well as of train journeys—sonic elements that likely introduced a pressurizing feeling.

We wanted to use this sound of the construction to also talk about these incomplete places, places that are being built, places that are erasing other places and how that’s kind of violent.

XUE, ‘a place we could not name’, transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

I feel that in a rapidly developing country like Singapore, where everything is constantly being renovated, built up, or built over, construction is an ever-present reality, the country is, in a sense, becoming a non-place—or one that is losing its meaning in the pursuit of what the state apparatus envisions Singapore to be. Therefore by including construction sounds, we can also draw attention to the inherently violent nature of a place that is always in a state of erasure.

After Razan and I play the game of “doors” with the audience, we grip onto the edges of the frame and rotate it while gradually increasing our speed, using the spinning momentum to fling our bodies onto the ground. Where we end up after this is purely a matter of chance.

A new frame, fitted with projectors on opposite sides, then slowly enters the space, pushed by Mervin. The projectors contain two videos, separate contributions by Razan and myself that cast images of water bodies, natural phenomena, and personal vignettes—clouds seen from a plane window, for example—onto the ground. As Mervin pushes the frame, he sings the song Bengawan Solo. To us, this moment evokes a lighthouse or a satellite. When the light touches our bodies, we begin to transform, guided by the emotional cadence of Bengawan Solo, triggering certain memories that shape our movements. This part of the work is especially intimate, as we abandon choreographic or performative intent entirely, delving into an inner world—one we hope the audience, too, can enter through the power of voice and their own heart spaces.

Perhaps the only semi-autobiographical element—or inside joke—is the choice to include Bengawan Solo, which I see as one of the keys to understanding this work’s artistic intent. The song whose namesake can be associated with the famous river in Solo, and the well-known bakery in Singapore all share the same name, yet each carries a distinct meaning. This layering of identities creates a semantic paradox—one term holding multiple realities at once. Bengawan Solo is not a fixed entity; it shape-shifts depending on context. I am drawn to this kind of symbolic dissonance—to things that resist singular definition. To me, every compelling work of art embraces contradiction, allowing meaning to shift and accumulate rather than settle into certainty. So what is Bengawan Solo, if not a paradox? Perhaps it is a palimpsest—a name rewritten over time, carrying traces of every meaning it has ever held. It is a name with many places. Apart from the inclusion of this song. We resisted including other signifiers or obvious cultural references. Rather than offering a straightforward narrative, the work invites the audience to encounter it as an unfolding or shifting space—something that demands a more personal, subjective response. Instead of resolving contradiction, it thrives within it, and that, to me, is where art becomes truly alive.

There were also “non-art” elements that shaped the piece on a more anti-authoritarian level. I only bring them up because they are important to me and my ongoing art practice in Singapore which deals with how I negotiate or work with local spaces. While we were rehearsing, the venue staff and sometimes passerbys would instinctively turn on the lights of the space, not understanding that it was our artistic decision to work in the dark. Their insistence only deepened my resolve to keep the lights off. Another challenge was the “glowing door,” which required the theatre door to remain open for an extended period—something almost unthinkable in Singapore, where an almost irrational anxiety surrounds the consequences of air-conditioning escaping. This hyper-awareness of containment and so-called “good sense” decisions felt deeply ingrained not just in space but in the fabric of Singapore. Within the piece, these concerns could be suspended or justified. The logic of the performance allowed for what would otherwise be considered impractical or unacceptable in daily life. It was as if the work itself created a temporary loophole—one where irrational choices could exist without immediate rejection. In a way, this felt empowering—an assertion that performance can construct its own reality, a space where the usual rules don’t necessarily apply.

In the early stages of this work, I confessed to my collaborators that we—or I—might be out of our depth, that the scope of the piece might be too broad to my current understanding of space and place. Yet Razan and Mervin chose to persist in this endeavor with me, asking questions that had no clear answers. For me, the process of finding the work—of trying to encounter its shape—was as invaluable as presenting it as something “good” or whole. It was an education in and of itself.

Reflecting on this work, I am drawn to questions of how performance can push further into sensory engagement and spatial awareness. The darkness, a crucial element, met resistance—some felt it was too much, others not enough. This highlights a challenge: how to make darkness an active material rather than a point of confusion. The work’s lack of clear cultural or conceptual signifiers left it open-ended, but should it have been more anchored? How do we shape an experience that is deeply felt rather than merely observed or unobservable? Moving forward, I want to heighten audience awareness of their senses, perhaps through more effective interventions, shifting the focus beyond sight. The site-specific nature of this piece also raises the question of its second life—how it can evolve beyond the *SCAPE Ground Theatre, into spaces with different constraints and affordances. The tension between hostility and invitation is another frontier: should the work resist comfort, or can discomfort be generative rather than alienating? And finally, how can the choreography be adjusted so that the subtleties of the body—tremors, twitching, micro-movements—are not lost and to what end?

In future experiments, I would like for us to continue to clarify our methods and deepen our research, in order for our ideas to fully manifest as material realities, not remain in the space of conception. The strategies we employ should not only provoke thought but create a tangible, bodily impact—felt rather than merely understood. This means refining our understanding and use of darkness, space, and sensory engagement so that the work is not just witnessed but physically experienced. How can we make audiences more acutely aware of their own agency within the performance? How do we activate other senses beyond sight, so that perception is not reliant on vision alone? I want to push further into the material conditions of performance—exploring texture, weight, temperature, proximity—so that the body is as engaged as the mind. Future works will also reconsider the relationship between performer, audience, and space, ensuring that the environment is truly an active force shaping and responding to the work.

‘a place we could not name’ invites ambiguity, discomfort, and openness. In my work, I often challenge the audience by disrupting familiar modes of engagement, using transdisciplinary approaches to create new systems and combinations. Our goal was to craft an experience that lingers—one that does not simply conclude when the lights come on but continues to resonate, introducing new perspectives in ways that extend beyond the performance space and into one’s lived reality.

Bibliography:

Wong Mervin, Wirjosandjojo Razan, XUE. “a place we could not name.” Transcript of artist dialogue, January 18, 2025.

Weschler Lawrence. Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees: Over Thirty Years of Conversations with Robert Irwin. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982.

Description of Work:

‘a place we could not name’ is an ongoing performance proposition that experiments with various processes of space-time intervention to materialize a site of transformation. The work seeks to explore place as a mutable construct, perpetually negotiated and redefined through the body’s engagement, marked by both its presence and absence.

Through provocations of body, sound, light, and object, stirrings of place rise and recede like waves on a shoreline; every arrival mediates a departure.

The project raises questions of agency and identity: How does the body choose to “place” itself in liminality, and how might it resist?

Performance Date/Times:

17 January 2025: 7:30PM – 8:30PM

18 January 2025: 2:30PM – 3:30PM (Artist Talk: 3.30PM-4:30PM)

18 January 2025: 7:30PM – 8:30PM

Venue: *SCAPE The Ground Theatre

Collaborating Artists:

XUE

Singaporean Butoh artist XUE is currently honing a transdisciplinary performance practice in Southeast Asia. Their performance-making practice is invested in the discovery and design of experimental frameworks that often take place as live situations or spatial assemblages. Deploying a choreography of interwoven agencies, XUE engenders an ecology of relations that favours indeterminate encounters, urging participatory bodies to contemplate the implications of space and body through the work's emergent and dynamic conditions and by proxy, their place in the world.

Razan Wirjosandjojo

Razan Wirjosandjojo is an artist currently living in Solo, Indonesia. He completed his studies in the Dance Department of the Indonesian Institute of the Arts Surakarta. Since 2018, Razan has studied with Melati Suryodarmo and is now involved as a member and staff at Studio Plesungan. With a background in dance, his work expands his perspective on viewing the body as a source of ideas and a vehicle, which he develops into performance art, performance, film, and photography.

Mervin Wong

Mervin Wong is a composer, music producer, and sound artist exploring deep listening and immersive sonic narratives. His work spans live performances, spaces, theatre, film/media and spatial audio, including Dolby Atmos mixing. Recent projects include composing the live score for a ‘place we could not name’ (2025) developed with artists XUE and Razan Wirjosandjojo, scoring and designing sound for National Gallery’s No Flash podcast (Season 2: Third Eye), and releasing Movement Landscapes (2023), a collection of works for dance and performance. Mervin also composed the genre-bending hyper-pop score for A Midsummer Night’s Dream (2023) with Singapore Repertory Theatre.

Support:

‘a place we could not name’ is a selected project of SCAPE Experimentation Ground, and supported by Dance Nucleus and Studio Plesungan as part of Artefact #13.

Thank You:

Padmini Chettur

Luke George

Melati Suryodarmo (Studio Plesungan)

Daniel Kok (Dance Nucleus)

Full Disclosure: I have copyedited aspects of the sentence flow and grammar in the artist talk for clarity while ensuring that my collaborator’s intended meaning remains unchanged.

By 'strange choreographies,' I mean sometimes absurd compositions that use multiple frames of reference, associations, and a non-linear logic."

I would like to note that due to the differing audience configuration and energy across all three performances, they played a big part in shaping the overall feel of the work.